inclusive design

paying people part 3

Last week we looked at why off the shelf software may ask for more information than is strictly required to perform its task. We thought about how this could cause problems and how we might be able to mitigate them by looking at parts of the journey that we have more control over.

Throughout this journey we’ve kept coming back to our different users and thought about how decisions we make can affect them, intentionally or not. This led us to changing the new starter form so we could provide a better experience for people joining Sow & Grow, our fictitious company.

By changing what we ask on this initial form, we can ask other questions at more appropriate times and it gives people the opportunity to answer these questions in a more considerate way.

Now let’s look at one of the outputs of a payroll system: payslips.

Payday and payslips

Rich: At the end of the month, Suze is eagerly looking forward to seeing their payslip so that they can do what most of us did when we got our first big pay slip. Treat themself to something nice.

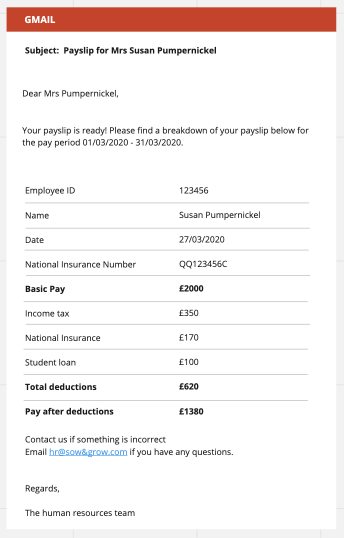

Things get a little hard going when they get the email and read it.

Before Susan has opened the email, they can see the consequences of completing the new starter form coming back to cause problems.

F: Yeah. If that were me, it would make me reluctant to even open it. I’ve left more than one letter unopened in a pile somewhere for exactly this reason.

Rich: When the email’s opened, there’s another instance of mislabeling as the payroll software was determined to use all the information it has and keeps calling them ‘Mrs’.

I think that when we create software it’s easy to think of all the what-ifs and ask for information that we don’t need for the software to function. We ask for these things because it can make us, as software creators, comfortable to have this extra information, even if we don’t need it or really plan to do anything with it.

It’s easy to think, “If we collect it now, then if we need it later, we’ll have it,” but it’s the difference between what we want and what we need. We don’t know what our needs will be later, so it’s better to build for our known user needs, and add more features when we understand what we need them for.

There are certain things in the email which are not needed for it to function as a digital payslip. This is fine if the user identifies with one of the limited set of gender options but if they don’t, then it can make this monthly check of the payslip something that causes apprehension rather than joy.

Fortunately we have control over the email and can choose what information we pull through from the payroll system. Rather than including a title in the email subject, we can say what the email is about. “Payslip for Mrs Susan Pumpernickel” becomes “Your payslip for March 2020”.

We can also remove the title from the beginning of the email. We’ve already talked about the need to maintain an air of formality in communications, but we wouldn’t address our colleagues as Mrs Pumpernickel. We would just call them Susan. To the user it’s still clear that we’re addressing them and for the business, we’re still providing that personal touch.

F: A slight aside here, but note that this approach relies on asking users for a first and last name, so you know what to call them without a title. If you use a combined full name field, it’s not reliable to make assumptions about how the words in a name split. Think Mary Jane Watson versus Vincent van Gogh. Or even what order they’re in. Consider the Japanese norm of putting the family name before the given name.

If you need to know how to refer to someone in correspondence with them, why not ask them for a preferred or contact name? We don’t have control over that in this system, but it’s something worth thinking about.

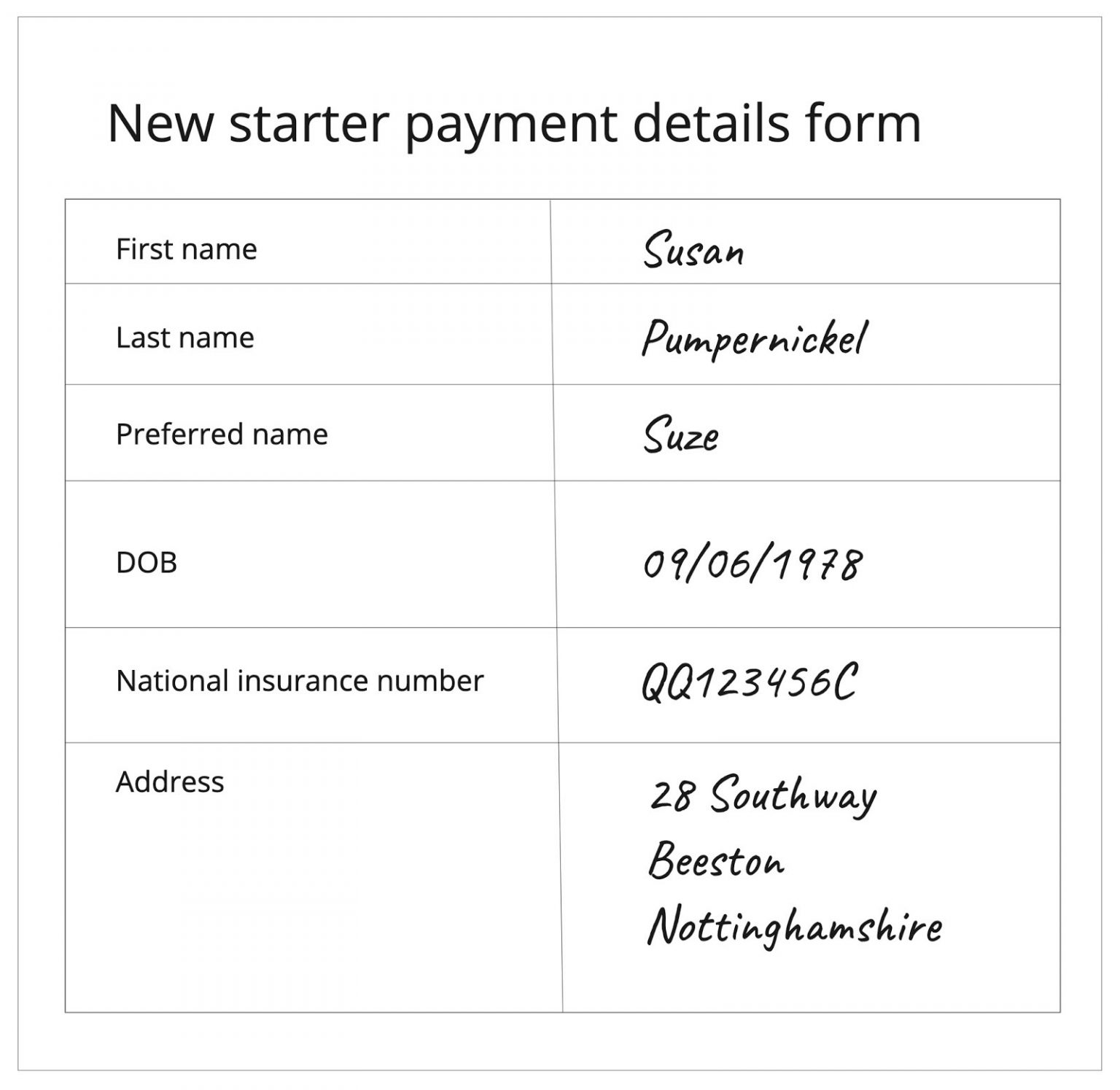

Rich: Okay, let’s capture their preferred name on the new starter form so we can call people what they actually want to be called.

F: That’s a great addition. It makes it clearer what the context for asking for names is. Suze can give details that are needed for identity verification and official correspondence, without expecting others to use a name they’re not necessarily comfortable with in less formal contexts. It would be even better with some guidance about where this information will go, but that can probably wait for another iteration.

Rich: So let’s use their preferred name in the payslip email instead of their full name.

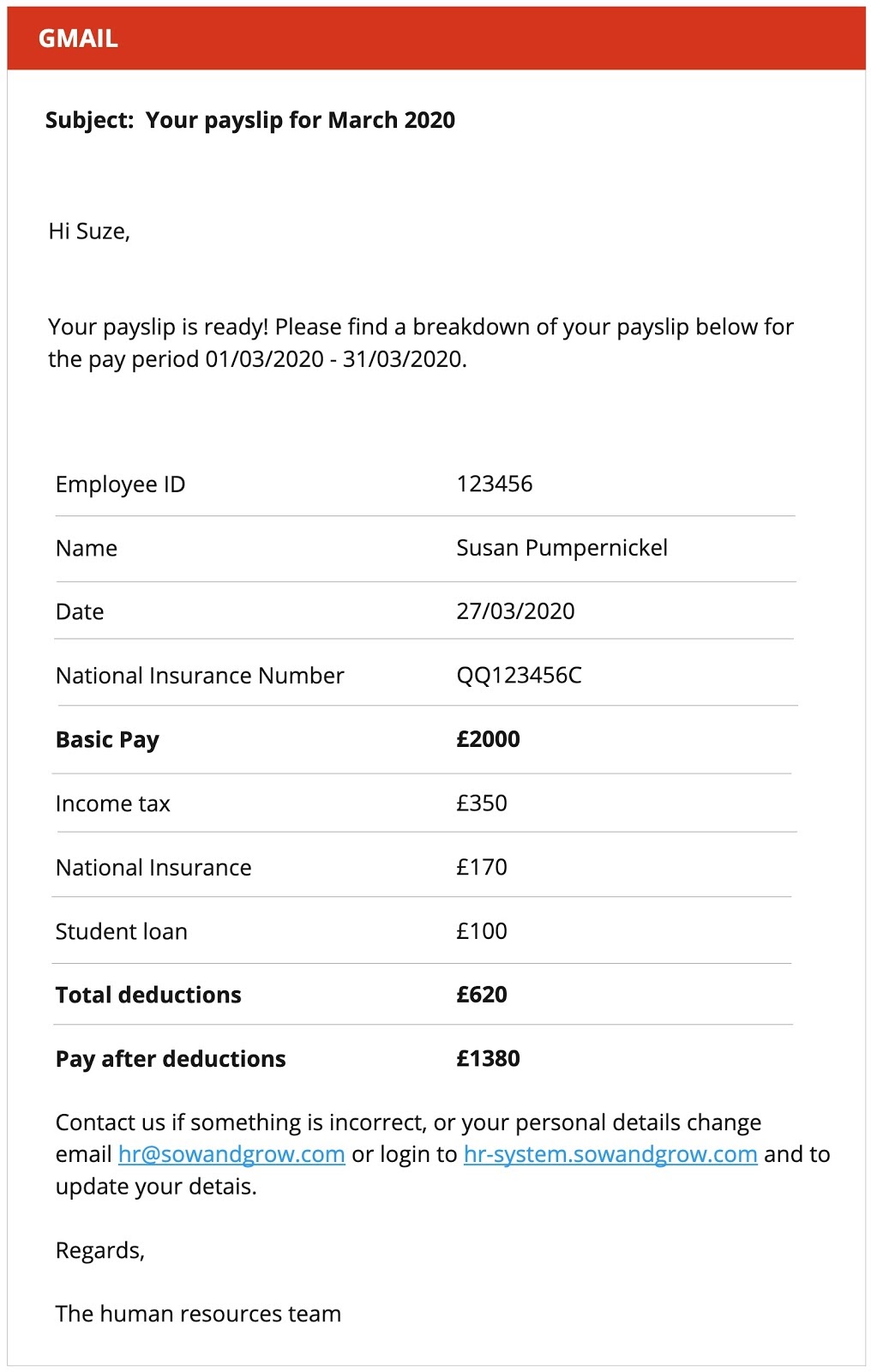

One good thing is that we don’t play back the recorded payroll gender. That’s not to say that the payroll system doesn’t have a gender recorded, or that the recorded gender is not shared where required by external systems. The main disadvantage I can see is if Suze’s identity shifted and they felt that they would prefer to be labelled by a different binary gender option. In this instance the information could become inaccurate and may stay that way for a long period of time.

This could cause a bit of mental anguish when they find this inaccurate information. It could bring up feelings of anxiety as they debate internally whether or not updating the records is worth having some potentially difficult conversations.

F: This is actually a bit double edged. You’re right that being constantly reminded about how systemically misgendered you are can be distressing, but how would Suze know that the data was correctly input for them? If they need to change it, how would they know that it had changed? If this information is being sent somewhere else, they probably need to know what was sent so they can make sure the data matches their records so they don’t fail other identity checks later.

Rich: That raises an interesting issue. We don’t want to keep misgendering people but we need to give them a way to find out what information we have recorded for them. Ideally we would also give them a mechanism to update the information that’s recorded, whether it’s an online form or a manual process. I think it may be best to allow multiple ways to amend the information, that way people can use whichever method they are most comfortable with.

There are many ways this could be done, for example:

- using an online portal to update their information

- speaking to a line manager or member of the HR team so they can update their information on their behalf

Iterate and improve

Here’s our improved email. We’ve tried to remove references to gender or title, call the recipient by their preferred name and add in guidance in case the information we play back is no longer correct.

F: This is so much better! The individual changes are small but they make a big difference.

Inclusive design is for everyone

It seems like we had quite a long journey and a lot of thought was involved in looking at a fairly small aspect of paying someone, adding them to payroll, and sending them payslips. I’m sure some people will look at this and think, “Was it really worth all that effort?” I think the answer is a resounding, “Yes”. When evaluating if something was time well spent, there are 3 metrics that can help:

- The amount of time spent changing something versus the amount of time users will save

- The amount of time spent changing something versus the reduction in complexity for users

- The amount of time spent changing something versus the emotional impact on users

With the changes discussed, it’s actually the human resources team that will save the most time. By allowing users to amend their information and by encouraging them to keep up to date information we can reduce the burden on staff to maintain the quality of employee records. Employees will also save time. By allowing them to input their own data, they skip the need to ask for corrections that only show up when they’re paid.

The third metric is a lot harder to measure, and may apply to fewer people, but is just as valuable. It helps people engage with the software, giving them ownership over their own information. And the benefit of these changes to Suze is huge. They can feel more comfortable knowing that they have the power to make changes to their information without having to have any awkward conversations.

The correspondence from work doesn’t misgender them, and if they want to find out what’s on the system they can log in and see. They’re more likely to check their payslips, allowing them to catch errors in their pay, tax, or pension contributions, which saves a lot of time and pain for everyone trying to correct them later.

Inclusive design makes things better for everyone.